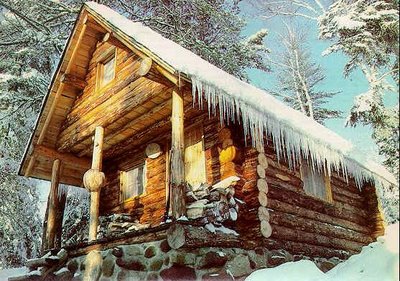

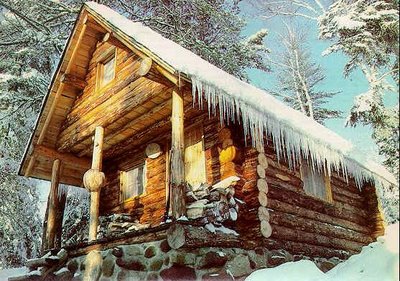

I have for many years dreamed of building a log cabin. From time to time I watch a video I burned to DVD -

Alone In The Wilderness. It is a documentary about Richard Proenneke, who built his own cabin in the wilderness near Twin Lakes starting in 1968, in what is now

Lake Clark National Park & Preserve in Alaska.

Alone in the wilderness, lost in the jungle, the boy is searching, searching!

The swelling waters, the far-away mountains, and the unending path;

Exhausted and in despair, he knows not where to go,

He only hears the evening cicadas singing in the maple-woods.

The Ten Oxherding Pictures, I. by Kaku-an

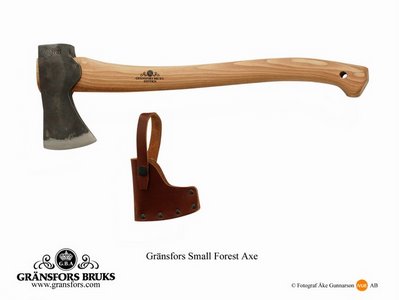

Select your logs. Straight, 8 to 10 inches in diameter, 16 foot logs, with minimal tapering.

Fell them in early winter as cool temperatures allow for slower drying periods, which reduces cracking and splitting, plus it is easier to haul the logs out of the woods over snowy terrain.

Season your logs - air-dry the logs for one to two years-the longer the better. Logs should be stacked off the ground with stickers-smaller diameter logs-placed between the courses. This allows for maximum airflow around the logs and promotes more even drying. You should also partially peel off the bark using a draw knife before the logs are stacked. This will increase their drying rate and cause only minimal cracking and splitting. However, before building begins, you must remove the remaining bark completely. It is a natural habitat for many different kinds of pests.

Many pioneer cabins were built without foundations because they were constructed in haste or meant to be temporary shelter. But a proper foundation is definitely required. Stone foundations traditional, but block and concrete walls are as good, or better, and they require less work.

If you don't want a full basement, you must excavate at least below the frost line, install footings and construct a wall up to 20 in. above grade level. You must also install piers within the foundation walls to support the floor girder. Also, install anchor bolts along the top of the walls to attach the sill. Begin floor construction by hewing or cutting flat the bottom of the sill logs. Then bore holes in the sill logs to accommodate the anchor bolts and install sill sealer or a termite shield according to the local building code. The corner joints are made by bottom notching the logs. Next, hew flat the top of the girder and install it over the support piers. Join it to the sill with a mortise and tenon joint. Drive 60d nails through the top of the tenon and into the mortise to complete the joint.

In a similar manner, hew or cut flat the top of the joists and install them between the girder and sill logs so they are flush with the top of the girder. Install the subflooring perpendicular to the direction of the joists. Now you're ready to start on the walls.

Many different types of notches can be used to join the logs, but a good choice for the beginning log builder is the technique shown here: the scribe, fit, round-notch method. It features semicircular notches cut in the bottom of the logs to fit over adjacent logs. Also, a V-shaped groove is cut down the length of each log bottom so the entire length can sit flush on the log below.

Although this method is slower than others, the corner joints are self-draining-water running down the outside of the house hits the log tops and runs off, instead of being trapped in the notch. The V-grooves also eliminate air drafts between the logs. The joints between courses do not need chinking, so you can avoid one of the most chronic maintenance problems of log homes: repairing cracked chinking.

Cutting the corner notches is a fivestep procedure:

- First, roll the log into position and sight along its length to make sure any crown is pointing to the outside of the wall. Try not to use logs that have more than a

1-in. crown per 16 feet of length. Then secure the log with a log dog as shown in the drawing.

- Scribe the shape of the lower, log onto the uncut log using compass dividers with a pencil or marking crayon inserted in one leg. Rough-cut the notch with a chain saw, then finish it with a shallowsweep, long-handled gouge.

- Reposition the log, allowing the notch to seat. Then scribe the full length of the underside of the log running the blank leg of the dividers along the top of the lower log. Scribe both sides of the log to yield the two lines which define the V-groove.

- Cut the V-groove with a chain saw to a depth of 1/2 to 3/4 in. Remove the waste, then roll the log back into

position and rescribe the corner notch as well as the log end extending past the notch. (By cutting the V groove, there is now some space between the scribed log and the one below.) Cut the notch to the new scribe line and cut the tail end of the log using a gutter adze. This tool yields a concave groove that is tighter and more attractive at the exposed log ends.

- Reposition the log, then pick up one end and drop it into place. This is called "thumping" and it will leave compression marks on the parts of the log that still need trimming. Make any necessary adjustments, then pack fiberglass insulation into the groove and roll the log into place. The fiberglass will act as a sort of "internal chinking."

With the notching complete, bore a 2-in. dia. hole about 8 in. in from each corner and insert an alignment peg. The peg should be loose fitting, recessed about 1-1/2 in. below the top of the hole, and extend about halfway into the log below. Install these pegs every 8 ft. in the length of a log and within 1 ft. of each window and door opening.

As you move up the walls, alternate each successive log so that their smaller, tapered ends are not all on one end of the wall. Once the logs reach waist height, cut out the door opening. Brace the logs on both sides.

Of course, if your cabin is larger than the one shown here, you'll have several interior partitions. These can either be made with logs notched into the outside walls or with framed walls later on. Notching the logs is preferred because it yields the same interior finish on all walls and strengthens the structure.

When the logs reach the top of your planned window and door openings, brace the walls and cut out all the openings at once. Then cut a groove, as shown, in the log ends on both sides for a permanent stiffening spline. Cut and insert the spline and then add at least two more logs over the openings. The top wall log is called the plate log and it should be pegged at least every 4 ft.

The roof on the cabin shown is a combination of purlin and rafter construction to give an idea of what's involved with both. Normally, you would use only one. The purlins are set into notches cut in the gable ends; the rafters are notched into the plate log and ridge log.

Once purlins or rafters are installed, apply roofing boards for the roof sheathing. Next, apply 15-lb. roofing felt and either asphalt shingles or cedar shingles.

Finally, pre-assemble all window and door jambs, install them in the openings, and add the windows and doors. Allow 3/8-in. clearance for each vertical foot of opening above the jambs for the logs to settle. The spaces around the jambs should be chinked with okum (hemp and pine tar).

Wash the logs with detergent to remove any dirt, and then with a solution of two parts household bleach to one part water to lift out any stains. Rinse the logs thoroughly with water and let them dry for a week. Then apply a mixture of one part linseed oil to five parts turpentine to the outside of the logs. This treatment should be repeated every five years.

(Note: This article has been updated and originally derived from a Popular Mechanics issue - December, 1983)

.JPG)